On EVs, Europe Mistook Market Signals for Demand

Brussels and National Capitals Needs to Learn about Whole Value Chain Planning to Stay Relevant

In the early days of Europe’s electric turn, the future arrived the way it often does on the old continent: as a folder. It had a title, an annex, a consultation period, and a gentle assumption that if the rules were correct and the incentives stabe, reality would eventually comply. Somewhere between a White Paper and a stakeholder roundtable, electrification became a matter of framework conditions. The market would do the rest. Consumers would respond to price signals, firms would innovate, utilities would build chargers when utilisation justified it, and the whole system would glide—more or less on schedule—toward decarbonised mobility. Such stories have died a slow death in the European corrdidors of power but their price tag is steep.

It was an attractive story during the crucial 2010s because it sounded like Europe itself: orderly, legalistic, allergic to command, with distributive investment and knowledge systems. Also, it worked just well enough in the places that already had everything. In Norway and the Netherlands, the transition felt almost boring: incentives were stable, chargers mushroomed everywhere, early adopters did what early adopters do, and the public got used to seeing silent cars at traffic lights. These countries became the photos on conference slides, the evidence that Europe was “leading.”

Meanwhile, elsewhere on the continent, the same policy architecture produced a very different sensation: EVs as an expensive bobo hobby and charging as a public policy distraction. A future that depended on income, geography, and luck was not really a future; it was a boutique market. This was particularly in Germany, where the liberals in the traffic colaition somehow managed to block the use of grants from Brussels and let the market do its magic with planting the charging infrastructure. It didn’t and Germans were left with a marked EV range anxiety problem ever since.

That gap—between the brochure version of transition and the lived version—was where demand management should have intervened. Not as propaganda, and not as another round of targets, but as an admission that electrification is a coordination problem before it is a technological one.

You can decarbonise the electric power sector with a handful of big investments, especially when the state owns the utility companies. You cannot electrify a vehicle fleet on w whole continent without aligning millions of households, thousands of municipalities, dozens of grid operators, and a finance system that usually prefers predictable returns to industrial upheaval. Weak EV demand management is one of those quietly structural failures that only becomes visible once industrial hierarchies have already begun to shift from Europe to China first slowly in the 2010s and then suddenly in the 2020s.

Europeans often prefer to narrate the continent’s EV lag through the language of technological competition: batteries, platforms, software. Yet electrification was always less about inventing the car of the future than about coordinating the conditions under which millions of consumers would actually buy it. Before it is a technological race, electrification is a systems problem. On that terrain, Europe hesitated exactly when China went all in: the 2010s.

Part of this hesitation reflects intellectual history. European policymakers remain instinctively skeptical of “planning,” a reflex shaped by the twentieth century’s encounters with command economies. Markets allocate; states regulate. Anything more directive risks inefficiency or capture. That caution is not irrational. It helped produce some of the world’s most competitive manufacturing sectors. But in the case of EVs it also generated a style of intervention that was visible yet shallow: generous purchase subsidies layered atop a coordination architecture that remained underfinanced and woefully fragmented.

Affordability and charging access were always the two hinges of mass adoption, and Europe leaned heavily on the first. Nearly every major member state offered consumer incentives: Germany’s Umweltbonus, France’s bonus écologique, tax exemptions, toll reductions. These measures lowered upfront costs and stimulated early adoption, particularly across Northern and Western Europe. In that narrow sense, Europe mirrored China. Yet the resemblance dissolves once one looks at policy design rather than policy existence.

By late 2025, as the so-called “Das Auto crisis” unsettled boardrooms, the European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association) published data showing how tightly battery-electric uptake tracked income levels. Wealthier countries with stable incentives surged ahead; poorer member states struggled to reach even 7 percent penetration. Poland briefly demonstrated the elasticity of demand — adoption rose when subsidies appeared and stalled when they vanished — a reminder that fiscal signals mattered, but only if they were credible over time.

Much has been made of subsidy differentials, China’s rule in critical minerals, cheaper Chinese labor (not so chap any more, closer to Poland if you go on the coasts), cheaper energy, land grants etc. We know all that. Brussels frequently notes that China deployed far larger support packages — estimates exceed €230 billion between 2009 and 2023 once producer grants, rebates, tax breaks, land concessions, and energy pricing are counted. China cheated, they say, and they put tarriffs on Chinese EVs.

But while China’s greater subsidy and critical minerals orchestration mattered, there are two problems with this argument: the green transition was pitched by Europe as being about massive state support and there is also no settled global rulebook defining “fair” clean-tech subsidies. This makes accusations of distortion analytically slippery. The harsh truth for Europe is that for decades China had intervened heavily in all kinds of sectors without triggering European tariffs because its firms did not threaten the commanding heights of European manufacturing. The alarm only sounded once electrification began to reshape the automotive core and Europe’s place at the top of the pecking order.

Be that as it may, the subsidy size alone explains surprisingly little. What mattered was policy conditionality. I know, bear with me.

Chinese fiscal support behaved like classic developmental-state discipline, the kind of stuff Japan and Korea practiced to get rich: the subsidies went to the EV companies primarily, not the consumers, and they came with steel strings attached. Eligibility was tied to technical thresholds such as battery energy density, electric range, and the use of domestically produced cells. The 2016–2019 “whitelist” Beijing used effectively forced manufacturers up the technological ladder by excluding EVs with short-range batteries. Firms that wanted subsidies had to build better cars with better batteries. Was this state paternalism? Some may call it that. But it created a feedback loop between policy, engineering, and scale, one that battery leaders such as Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited quickly learned to exploit and become the world’s largest battery company.

European subsidy schemes were more like handouts. Germany’s Umweltbonus, for instance, subsidized both EVs and plug-in hybrids at broadly comparable levels for years. France followed a similar path. The reluctance to impose strict performance discipline reflected a deeper political economy: governments were wary of destabilizing domestic automakers mid-transition. With less autonomy from business than the CPC, European states complied.

The result was predictable. Automakers scaled plug-in hybrids because they were cheaper and less technologically risky than long-range electrics. Real-world emissions from these vehicles often exceeded certified values by multiples, but the learning effects that drive long-term competitiveness accrued elsewhere on the souther cost of China, not in Bavaria.

By 2019 roughly a third of European battery vehicles still offered real-world ranges below 250 km. Early models from incumbents lagged far behind competitors such as BYD Company, whose vehicles increasingly defined the technological frontier. Average Chinese ranges overtook European ones not because engineers were inherently superior, but because policy refused to subsidize mediocrity.

The way Europeans and the Chinese used state finance widened the divergence. If decarbonization speed is endogenous to coordination capacity, then credit allocation becomes industrial policy by other means. China’s statebanks supplied abundant, cheap capital across the EV value chain, from upstream materials to… consumer loans.

In contrast, Europe’s public lenders behaved more cautiously. The European Investment Bank and Germany’s KfW supported electrification projects, but mostly through conventional banking logic: risk assessment, co-financing, incremental deployment. Credit lines existed for corporate fleet electrification and some charging infrastructure, yet the volumes were modest and consumer lending at promotional rates never materialized at scale.

Equity finance revealed an even sharper contrast. Chinese local governments and government guided funds deployed patient capital to cultivate national champions, while Europe largely waited for private investors to shoulder technological risk. Its financial apparatus was extensive but fragmented, but less capable of supporting projects, less capable of underwriting transformation.

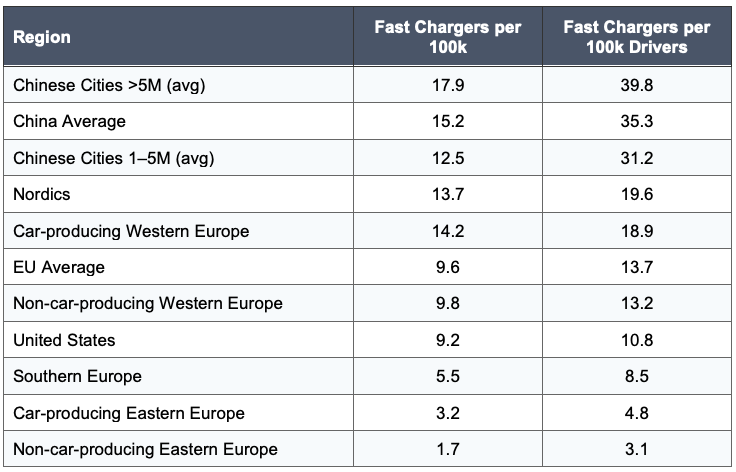

The charging infrastructure exposed the coordination gap most visibly. Both Europe and China recognized early that range anxiety could stall adoption. But while China embedded charging into national planning, Europe treated it as a market expected to mature organically. The results for Europe captured another instance of delayed development vis-a-vis China, as my calculations in the table show.

Even in Germany, during the pivotal late 2010s, a study concluded that investments were “not being made due to the lack of economic profitability of charging stations” and that

“The expansion is usually limited to model projects marketed in the media or to a few very innovative companies and municipalities. Moreover, as CSs are subsidized, companies may be using the installation of charging infrastructures primarily for image and marketing purposes to meet the social need for increased environmental awareness” (Zink et al 2020: 195).

China’s central planners issued a comprehensive infrastructure strategy as early as 2015, and the numbers tell the story: by 2023 the country had installed roughly three million public chargers, including hundreds of thousands of fast units along highways and dense urban corridors. Utilities, municipalities, automakers, and battery firms acted in synchrony, often under deployment targets that doubled as bureaucratic performance metrics. Large grid operators received explicit expansion guidelines; local officials were evaluated on delivery. Charging was not an adjunct to electrification — it was its backbone.

Europe produced something closer to a mosaic. Norway and the Netherlands built dense networks; Southern and Eastern regions lagged. Public chargers numbered in the hundreds of thousands rather than millions, and fast chargers remained comparatively scarce. Cross-border continuity along major transport corridors proved uneven. Drivers navigated a thicket of payment systems, subscriptions, and reliability standards. Competition flourished; cohesion did not.

The roots of this patchwork lie in institutional philosophy. Early frameworks culminating in the Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Directive relied heavily on national planning rather than binding mandates. Funding instruments prioritized pilots and interoperability, assuming markets would scale once viability was demonstrated. Auditors later noted the absence of a comprehensive infrastructure gap analysis — policymakers could not specify how many stations were needed, where they belonged, or at what capacity. Investment gravitated toward commercially attractive markets, leaving peripheral regions underserved.

Only after the competitive shock from Chinese EV exports did Europe pivot toward stronger directive tools, such as minimum spacing requirements along the trans-European network, a subtle but meaningful shift toward hierarchical coordination. By then, however, the temporal advantage had migrated to the manufacturing superpower in the East of the map.

None of this implies that Europe chose wrongly out of ignorance. Its approach reflects durable commitments: competition policy, fiscal restraint, political consent, technological openness. These are not trivial virtues. But they generate a procedural style of authority: states construct frameworks and safeguard markets rather than commanding outcomes. Electrification, it turns out, rewards systems comfortable with synchronization. The Greenland and the China shocks combined seem to be waking Europe up to this new reality and some are already dusting off old European books about how postwar French planning gave the world the high speed train, Airbus or nuclear power at scale though a state that know how to plan under a contested democracy and a largely capitalist system.

Electrification did not simply reward technological leadership; it rewarded institutional architectures capable of aligning subsidies, finance, infrastructure, and industrial strategy at speed. China confronted the transition as a problem of whole value-chain organization. Europe approached it as a regulatory challenge and only gradually discovered that markets do not coordinate themselves fast enough during technological regime shifts.

Skepticism toward planning remains justified. The European memory of overcentralization is not something to discard lightly. Short of federalizing Europe, whole value chain orchestration in automotive would be like herding cats, particularly under political polarization, MAGA inroads in European politics and a toxic digital media environment.

But Europe’s EV transition woes suggest an even more uncomfortable conclusion: the relevant divide today is no longer between plan and market, but between systems that can orchestrate complexity across both supply and demand curves and those that hope competition with a bit of subsidisation will eventually do the job. Europe seems to play the latter game, holding weaker cards than China, particularly in demand management. Europe could have used its trillions in demand subsidisation (the Commission budget, state aid, government bank promotional credit, the grants from the special fund established after Covid via joint borrowing) without even compromising much of its internal politics. Blanketing Europe’s roads with high speed chargers as a form of European public infrastructure using direct public works would have cost tens of billions not trillions.

With factory closures and orders drying up across the whole European automotive value chain, there should be great certainty that Europe’s demand management engines are failing and need to be taken to a more imaginative mechanic. Having mastered a century of internal combustion propulsion, Europe should know that technology revolutions come with lock-in effects, otherwise known as wealth privileges for whoever controls those revolutions during their early stages.

It is funny to witness that once we start losing, we accuse the other of not playing fairly. May someone define it, please? What is worrying is that the public discourse is dominated by this narrative which leaves little to no space in questioning what we have done wrong in the EU. Reflecting inwards than directing our anger outwards may be a first step, though we are reluctant to accept it.

'early adopters did what early adopters do'

Mind you, the Dutch gov subsidized the hell out of them. Dutch early 'adopters' driving Teslas were business men who previously drove Jaguar or BMW. Meanwhile fossil drivers were literally taxed to finance Tesla drivers subsidies.

The Dutch gov pulled in Tesla's European assembly 'plant' with 'green incentives' i.e. subsdies and tax exemptions - creating a few hundred jobs.

In total the gov spent 13 B euros on Tesla and its wealthy buyers. The year the gov ended the subsidy schemes Tesla left for Germany. Another nation with a middle- and upper class high on virtue signalling via other people's money.